India’s monsoon rains have finally arrived, touching down on the coast of India’s southern Kerala state on June 7, a week later than normal, marking its latest arrival since 2019. The annual monsoon is considered the driving force and energy of the Indian economy, delivering rains essential to agricultural production and replenishing water reservoirs that provide vital drinking water and support power generation.

Almost half of India’s farmland depends heavily on the June to September rains, which generally account for about three-quarters of the country’s agricultural production requirement. The monsoon is not only essential to non-irrigated Kharif crop production such as rice, cotton, corn, soybeans and sorghum; it also sets the soil moisture scene for the Rabi crops such as wheat, barley and many pulses which are sown after the monsoon has receded.

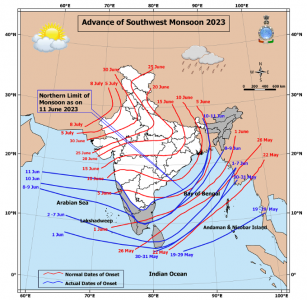

The Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) was originally expecting the monsoon to hit the southwest coastline on June 4, but the onset was delayed by the formation of a severe cyclone named Biparjoy over the east-central Arabian Sea.

According to the IMD, precipitation across India was just 43 per cent of the average for the first week of June, reflecting the late arrival of the monsoon and delaying the Kharif crop planting program in some regions. The monsoon is expected to progress slowly northward, but the IMD expects the central and northern regions to remain relatively dry for the next two weeks (see IMD graphic).

The arrival of this season’s monsoon coincided with the US weather agency National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) ‘s confirmation that El Nino had officially formed and was likely to strengthen throughout the northern hemisphere summer and autumn. This means the entire monsoon season will likely be in the presence of a strengthening El Nino.

The El Nino weather phenomenon is marked by abnormal warming of waters in the eastern central equatorial Pacific and changes in global wind currents, which can lead to poor summer monsoon rains in India.

NOAA stated that conditions over the Pacific Ocean in May met all El Nino parameters, including sea surface temperatures at least 0.5 degrees Celsius above average, continuing wind anomalies and enhanced rainfall along the equator, favouring below-average rainfall throughout the monsoon season. The IMD is expecting rain this season to be 96 per cent of the long-term average, with registrations in the 96-104 per cent range deemed “normal”.

Over the last century, India has experienced 18 drought years since 1900, 13 of which were associated with an El Nino. In the past 70 years, the El Nino weather pattern has occurred 17 times, with India experiencing average or above-average monsoon rains on six occasions. However, in six of the seven El Nino years since 2000, the monsoon rains have been below normal, with the exception being 2006, when the El Nino developed in late September. And five of those six dry years were classified as drought years with rainfall less than 90 per cent of the long-term average.

Meanwhile, last week the Indian government announced the Minimum Support Price for kharif crops for the 2023/24 season, but farmers are already concerned that the proposed increases are not keeping up with rising input costs. The MSP for common paddy rice has been set at 2,183 Indian Rupees per quintal (AU$393 per metric tonne), up seven per cent on the 2022/23 price and the second steepest increase in the last decade. The maize MSP was increased by 6.5 per cent to INR2,090qtl (AU$376/MT), medium staple cotton saw an 8.9 per cent hike to INR6,620/qtl (AU$1,191/MT), and soybeans received a 7 per cent increase to INR4,600/qtl (AU$827/MT).

On the Kharif production front, the USDA’s June update pegged 2023/24 rice production at 134 million metric tonne, up from 133MMT in the May report but down from 136MMT in the 2022/23 season. There has been a trend to rice at the expense of soybeans, cotton, sugarcane and some pulses in recent years due to higher prices and the comfort of a Minimum Support Price for government purchases. Domestic rice consumption is expected to be 114MMT in 2023/24, up 1MMT month-on-month and 1.5MMt higher year-on-year. The USDA is currently calling rice exports 23MMT, up from 22.5MMT in its May report and 22.5MMT in the 2022/23 season.

The Indian maize crop forecast from the USDA for the 2023/24 season is unchanged compared to May at 34.3MMT but slightly lower than the 36MMT produced in the season prior. Domestic consumption and export forecasts were 31MMT and 3.6MMT, respectively, both unchanged from May but down from 32MMT to 4MMT in 2022/23.

The USDA is calling 2023/24 soybean output 12MMT, which is in line with both the May estimate and the 2022/23 crop, and the crush is expected to be 9.8MMT, unchanged month-on-month but down from 10MMT in 2022/23. The current cotton crop forecast is 10.83MMT, the same as the May estimate, but up slightly on the 10.61MMT produced last season. Sorghum output is the same as May at 4.4MMT, but up 10 per cent from 4MMT in 2022/23.

With a general election expected in the second quarter of 2024, Prime Minister Narendra Modi is treading a fine line between controlling food inflation, which the government says is now in a declining trend, and keeping the country’s countless farmers happy. No doubt Modi will be praying that the 2023 monsoon can keep a prying El Nino in check.

Call your local Grain Brokers Australia representative on 1300 946 544 to discuss your grain marketing needs.